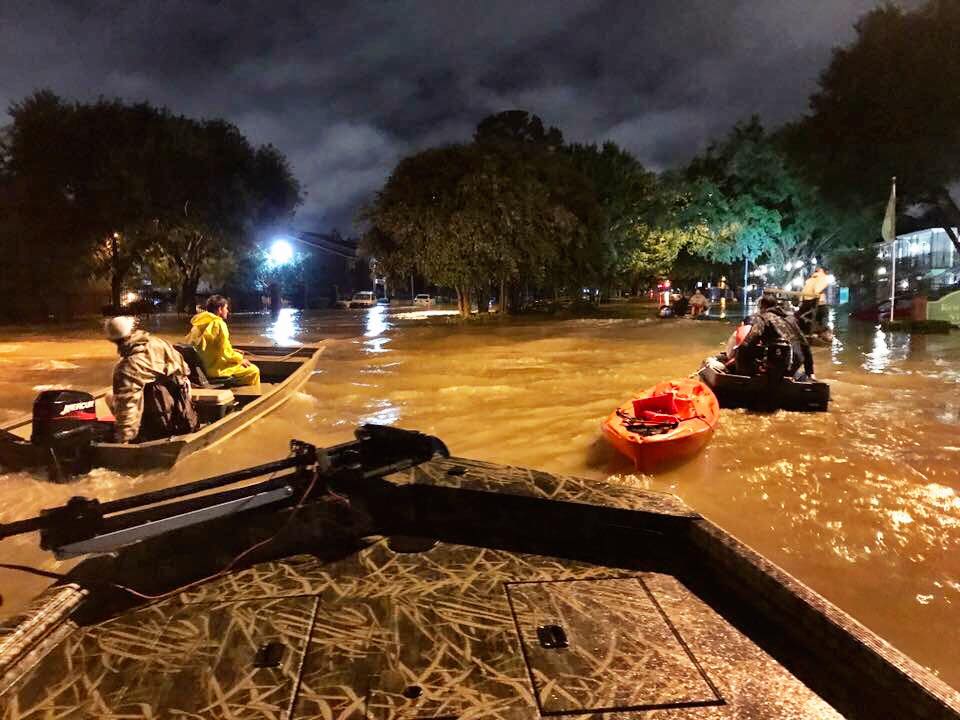

The view from Dr. Jared Wood's flat-bottomed boat as he navigates flooded roads and neighborhoods in the Houston, Texas, area on Aug. 27, 2017 Photo by Jared Wood

When the world woke up Saturday morning, Aug. 26, 2017, to news about a raging Hurricane Harvey, many dropped to their knees to pray. Many wanted to help. But how do you help in such a situation?

Jared Wood, biology professor at Southwestern Adventist University in Keene, Texas, has spent many of his 29 years in small boats, navigating waterways around Oklahoma, Texas, Kentucky, and Florida as a field biologist. When he saw the devastation flashing across his computer screen and all the requests on social media for boats, he knew there was one way he could help. Wood called everywhere he could think of, including the Harris County Fire Marshal, Galveston County Sherriff, Texas Search and Rescue, and the Coast Guard. No one answered at first, so he kept trying. While he was waiting, he packed.

"How can I help?" Wood asked when he finally got through to Galveston County Sherriff’s office. He explained that he had a flat-bottomed boat (necessary for navigating shallow, flooded areas) and outlined his experience in the water.

The sheriff's office replied, “Please, come help. And bring your boat.”

Packed and ready, Wood kissed his wife and kids goodbye at home in Burleson and headed for Galveston. But he couldn’t get through. All the roads were impassable. Wood began looking for another agency that might need help and discovered the Zello app that allowed him to communicate with Texas Search and Rescue. They said they could use him in the northern Houston area.

Adjusting his course, Wood tried to get there, but again the roads were nearly impassable and the sun had already gone down. He pulled up to a corner store, just as a few other trucks and boats pulled up. They, too, were having trouble getting close enough to help. They decided to band together, with six boats and 13 people.

Photo by Jared Wood

Texas Search and Rescue (TSR) gave the group another area to try. Their first assignment was an apartment building where people were stranded on the second floor. The floor was beginning to collapse.

Their second call was to a family caught in their home. And on it went through the night. The group checked every submerged and stranded car. They heard radio dispatches for many pregnant women, snake bite victims — and a family trapped in their home with alligators surrounding them.

It was rough going — it was pitch dark and the roads were constantly changing from dry or shallow to deep, urban rivers with treacherous currents. Some of the smaller boats struggled against the currents. They were able to help some people, while other times they were thwarted, no matter how many different routes they tried, by the raging waters. If they couldn’t reach them and the situation was dire, TSR radioed for a helicopter. If the situation wasn’t dire, sometimes the people were told they had to wait until bigger boats were available.

The Next Morning

Around 5 a.m., the group went in for fuel and rest. A short time later, Wood met up with another group to search a new area. The rescue teams were still mostly civilians, using social media, radio apps, and word-of-mouth to find those in need of help. There were several staging areas set up through the morning, as the civilians sought to better organize themselves.

They were able to help some families get out and determine where others had already been rescued. Water levels continued to rise and the currents grew stronger. Further complicating the situation was incorrect or old information and news of armed looters disrupting rescue efforts. The volunteers had to stay in groups for their own safety.

“We had a lot of help,” says Wood. “It was amazing how many people volunteered their time and boats. Even the local fire departments were using civilian boats.”

Later in the afternoon, Wood went to a new staging area where civilians were working with local police. The volunteers were paired up and sent out to certain sections in the Woodlands area. But now, the water was flooding the area so fast that authorities didn’t have time to issue mandatory evacuations. The currents were too strong for the smaller boats, including Wood’s, and even larger boats with large engines were struggling.

“Working with the fellow volunteers was a good experience. People were offering up whatever they had, even though they didn’t have much themselves,” says Wood. “There was such comradery.”

Photo by Jared Wood

Working Together

Wood worked on dry land for a while, helping people haul their possessions and animals to safety, guiding those rescued to safe places, and passing on addresses with requests for help. Later in the day, he was asked to once again go out with his boat, this time to scout waterways that the larger boats could use to access isolated neighborhoods.

“The hardest part of the experience was realizing how huge the problem is, how many people need help, and not being able to get to them because you don’t have the right equipment.”

Coming back for a break, he stopped at his truck and suddenly realized that his whole body was cold and trembling. His last pair of dry clothes were soaking wet, despite wearing chest-high waders. He had packed three days’ worth, and he had already gone through them all. Someone approached him with some hot food and a towel. It had been like that all day, other volunteers and locals offering food, towels, and even a place to rest in their homes.

As another day was coming to an end, the local authorities started pulling many of the boats out of the rescue effort. The water was still rising, the currents were too strong, and some of the rescuers had to be rescued themselves.

“You have to use your skills and abilities intelligently," explains Wood. "I did not leave my driveway until I received word from officials that my skills and supplies were needed. On the other end, it is hard to have to decide when you’re no longer a solution and need to leave so you don’t become a part of the problem. There came a time when we had to step down from our efforts.”

Wood made the call to head home. His boat could no longer handle the strong currents. The Coast Guard and National Guard were taking over many of the rescues because only their equipment and boats could reach many of the remaining locations. By now, there were also hundreds of volunteers with their boats all over Houston and the surrounding cities. Wood had done as much as he could. It was time to let others lead the effort.

“It was worth it. There were so many people trying to do whatever they could to help. The response was so much faster than I’ve seen at other disasters," Wood says. "There are a lot of people out there helping other people.”

***

Many people want to help. While it is not possible for everyone to physically help in the impacted area, there are ways you can help too. Consider donating to Adventist Community Services (ACS). Southwestern Adventist University is partnering with ACS to assemble disaster relief kits, but more supplies are needed. The supplies for these kits are very specific, pre-approved items by Emergency Services. The best way to help is to donate so that ACS can purchase the supplies. Students are anxiously waiting to assemble more kits.

You can also make donations by calling 1-800-381-7171; or mailing to Adventist Community Services, 12501 Old Columbia Pike, Silver Spring, MD 20904-6600. Please continue to join us in prayer for every one impacted by Hurricane Harvey.

— Darcy Force is the director of Public Relations and Marketing at Southwestern Adventist University; this article originally appeared on the SWAU website.